Genetic and epigenetic regulators of pollen and germline development

We use a combination of molecular biology, single-cell sequencing, and computational and statistical tool development. Wet-lab projects are exclusively in plants, but we work on computational projects in animal systems through collaborations. Check out some of our projects below!

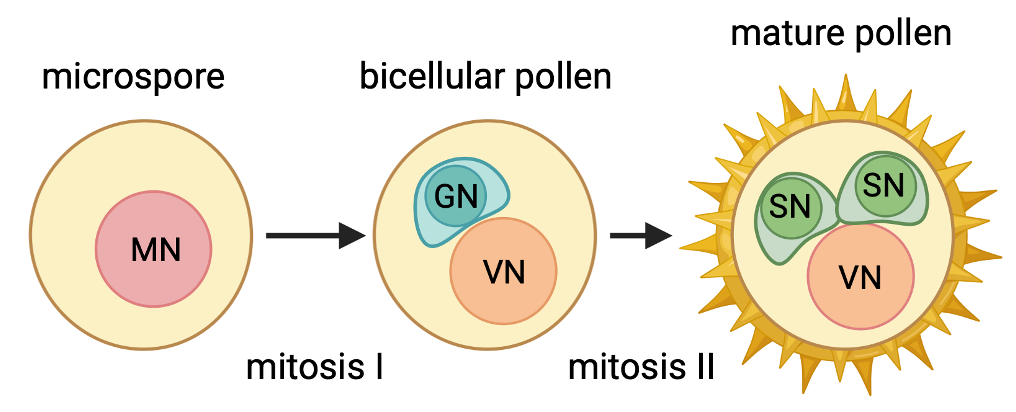

Most plants that you see around you, including most crops that we consume, make pollen in order to reproduce. In the small model plant Arabidopsis, mature pollen is a multicellular, haploid organism containing only three cells. Despite the simplicity of pollen development, it shares a lot of developmental paradigms with more complex multicellular plants and animals, including asymmetric division, cell fate differences, and epigenetic reprogramming. Pollen is also easy to isolate, stage, and image, in addition to being important agronomically, making it a great system in which to study basic developmental regulatory mechanisms.

The development of a multicellular organism is a complex series of interactions between individual cells. Over the past few years, advances in sequencing technology have made it possible to capture the behavior of individual cells (or nuclei) in a multicellular organism across a range of developmental states. We’re applying this approach to Arabidopsis pollen to find new potential regulators expressed at key timepoints during development.

Most of the staple crops grown worldwide are seed crops, where the part we consume is the seed (rice, corn, and wheat, for example). Each of these seeds requires successful pollination. But although all stages of plant development are vulnerable to heat stress, early pollen development is particularly sensitive. In crops, this means that a poorly timed heat wave can dramatically reduce yield – and climate change is making this a growing concern. Building on the Arabidopsis pollen single cell sequencing data (see section above), we are trying to figure out what goes wrong in heat-stressed pollen, with the long-term goal of improving crop fertility and resistance to yield reductions in the age of climate change.

Over the past 5-10 years, there has been an explosion in the generation of sequencing datasets at the single-cell level. These data can tell us a lot about the behavior of individual cells in complex systems and developing tissues, but pose unique challenges for data analysis compared to traditional bulk sequencing approaches. For example, single-cell sequencing datasets are very sparse, with lots of variability and missing data that are hard to properly account for. This makes it hard to figure out a good modeling approach to measure different features of the data. Another challenge is visualization – a single typical single cell transcriptome dataset includes information about the expression of >30,000 genes in each of >10,000 cells. How to represent this data in a way that the human brain can understand without losing important information or creating misleading associations? One focus in my lab is on developing new statistical frameworks and visualization tools for single cell sequencing data, with a focus on the sorts of developmental questions we are asking in the lab (for example, how to identify candidate genes that may be involved in developmental transitions, when that transition is confounded with something that has a strong transcriptional signal by itself, like cell cycle phase – as is the case for asymmetric division).

In collaboration with experimental labs, we also do some data analysis work focusing on C. elegans germline development! Check out this recent paper for an idea of the types of projects the lab will be working on: Kirshner JA*, Picard CL*, et al. (2025) Sci. Adv. PMID: 40540580